To communicate anything there has to be a recognizable set of symbols which both parties are familiar and conversant.

In human language we talk about symbols cultures have created and utilized to convey meaning. Some written languages have symbols that represent the sounds of spoken language. Some symbols represent discrete sounds (alphabets) and some represent syllables (syllabary). Some written languages use the symbols to convey meaning that may not be directly related to sounds or may allow different spoken sounds for the same symbol (pictographic).

For the purposes of this paper I will stick to alphabet languages and use them to relate to other fields and concepts.

In alphabet languages each letter normally represents a particular sound and combinations of letters make more complete sounds like syllables and words. Letters may be combined in a myriad of ways to depict vast numbers of words and meanings.

So too, syllables may be combined in a variety of ways to depict words.

And then words combine to make phrases, clauses, and sentences.

And sentences combine to make paragraphs. And from there we are off to a wide variety of discourse types each laid out to present particular bits of information.

So too with numbers and the language of math and of programming.

Numbers stand alone and relate to other numbers and combine to form specific functions and can be modified by their relationship to decimal points and whether they are on the line, raised above it or lowered below it. Usually, discussions refer to combinations, whether letters or numbers, the value of those in relation to other letters of numbers, and the relationship of those structures to other combinations and groups of combinations.

So, generally, for math discussions not often do folks talk about a single number without mentioning in what context that number or number phrase is found.

So too with letters and words. What those mean is best understood in the context of their presentation. As such, it is more useful to talk not so much about the word as the use of the word in the context of the phrase, clause, paragraph or larger grammatical structure.

So too with punctuation and its relation to the surrounding grammar and the context it is found in.

For instance, in Luke 4 we have a comma whose value so far is 2,000 years.

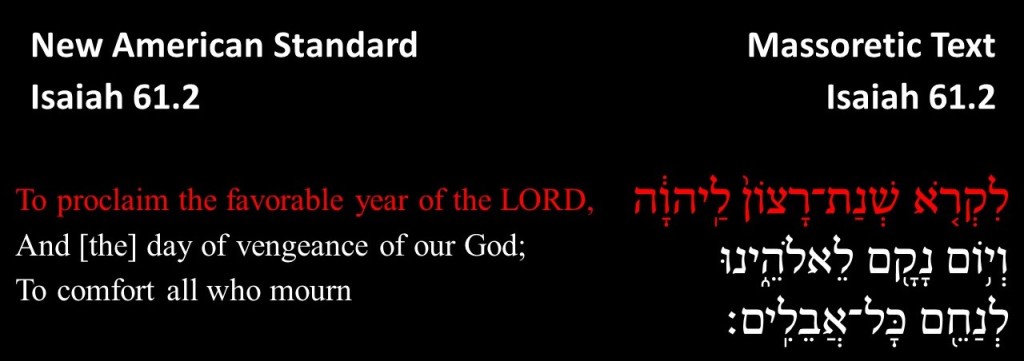

There we find recorded that Jesus went to his hometown synagogue in Nazareth (small village) and he stood up to read from the book of Isaiah. (Side note – small village synagogue has a copy of Isaiah. More than good chance that small synagogue has then entire TaNaK/OT). The passage is from Isaiah 61.1-2a. The literary extent of the passage extends to verse 11.

In the New American Standard I am looking at, in the Isaiah passage there is a comma at 2a separating it from 2b. The Massoretic notation in the Hebrew text has a zaqeph qaton which is somewhat analogous to a comma.

So why did Jesus stop at 2a?

Contrary to what the Pharisees et al expected, Jesus made the point that the Messiah would First come to Serve and then he would come to Rule. The pause in the passage is the pause between the First Coming Serving Messiah and the Second Coming Ruling Messiah.

As it is, that Comma represents right around 2,000 years!

This is a hint that in other passages there may be found chronological pauses or gaps if we pay attention to the whole of Scripture and pay close attention to the grammatical structure each biblical author was moved to use when the Holy Spirit used them to write God’s Word.